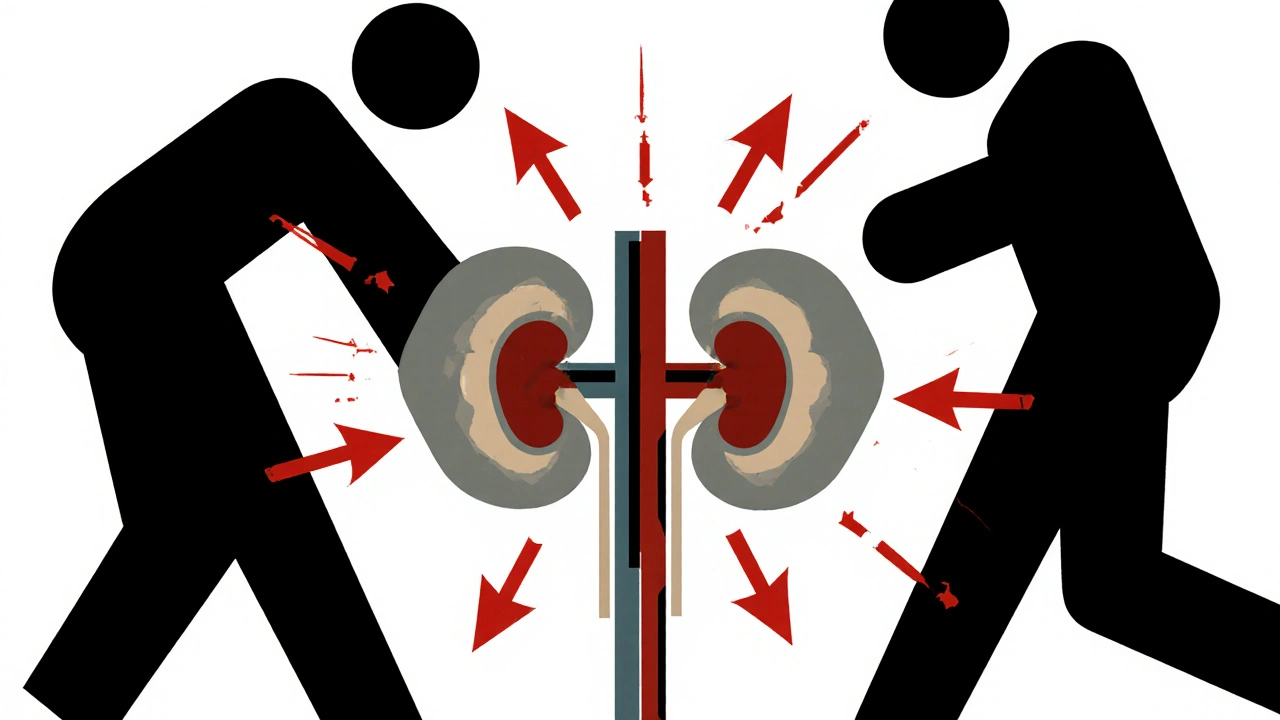

When your kidneys stop working, it’s not sudden. It’s a slow leak - a quiet breakdown that often goes unnoticed until it’s too late. Every year, tens of thousands of people in the UK and around the world reach end-stage renal disease (ESRD), where their kidneys have lost 90% of their function. At that point, dialysis or a transplant becomes the only option. But most of these cases aren’t random. They’re the result of three main enemies: diabetes, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis.

Diabetes: The Silent Kidney Killer

Diabetes doesn’t just affect blood sugar - it wrecks your kidneys. Over time, high glucose levels damage the tiny filters inside your kidneys called glomeruli. These filters are designed to let waste out while keeping protein and blood in. But when blood sugar stays too high, they start leaking. First, it’s just a little protein in the urine - something most people never notice. Then, the damage builds.

By the time someone is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, many already have early kidney damage. Studies show 40% of people with type 2 diabetes develop diabetic kidney disease within 10 years. The kidneys try to compensate at first, filtering more blood than normal - a state called hyperfiltration. But this only speeds up the damage. The walls of the glomeruli thicken, the filtering cells (podocytes) die off, and scar tissue forms.

The good news? Early action works. If you catch protein in your urine early - even just a little - and get your HbA1c below 7%, you can cut your risk of kidney failure by more than half. Medications like SGLT2 inhibitors (such as dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) don’t just lower blood sugar. They actually protect the kidneys by reducing pressure inside the glomeruli. In trials, they lowered the risk of kidney failure by 32%. That’s not just a number - it’s years of life saved.

Hypertension: The Pressure That Crushes

High blood pressure is the second biggest cause of kidney failure. And here’s the twist: it often hides in plain sight. Many people with hypertension feel fine. No headaches, no dizziness - just a silent, steady rise in pressure that slowly crushes the blood vessels feeding the kidneys.

When blood pressure stays above 140/90 mmHg for years, the small arteries in the kidneys harden and narrow. This is called nephrosclerosis. Less blood reaches the filtering units. The glomeruli starve, scar, and die. Over time, up to 40% of them can be destroyed. And here’s the worst part: hypertension and diabetes often team up. Three out of four people with diabetes also have high blood pressure. Together, they speed up kidney decline by nearly double compared to diabetes alone.

Controlling blood pressure isn’t about feeling better - it’s about saving your kidneys. The target for people with kidney disease is now <130/80 mmHg. For those with protein in their urine, it’s even lower - <120/80 mmHg. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are the go-to drugs because they don’t just lower pressure - they reduce protein leakage and slow scarring. But adherence is a problem. Nearly half of patients stop taking these meds within a year, often because they feel fine. That’s the danger. You don’t feel the damage until it’s too late.

Glomerulonephritis: When Your Immune System Turns on Your Kidneys

Unlike diabetes and hypertension, glomerulonephritis isn’t caused by lifestyle. It’s an immune system betrayal. Your body’s own defenses attack the glomeruli, treating them like invaders. The most common form is IgA nephropathy - where a protein called IgA builds up in the filters, triggering inflammation.

People with this condition often notice blood in their urine after a cold or sore throat. It’s easy to dismiss as a passing bug. But if it keeps happening, it’s a red flag. About 20-40% of people with IgA nephropathy will eventually need dialysis - but only after 10 to 20 years. That’s a long window to act.

Other forms, like lupus nephritis, come with autoimmune diseases. In lupus, the immune system attacks multiple organs, and the kidneys are often hit hard. Class IV lupus nephritis - the most severe type - has a 29% chance of leading to kidney failure within 10 years.

Treatment is different here. You don’t just control blood pressure or sugar. You need to calm the immune system. Steroids, rituximab, and newer drugs like sparsentan (expected approval in 2024) target the inflammation directly. But there’s debate. Some doctors argue that aggressive treatment in older patients does more harm than good, increasing infection risks without saving kidneys. Others say delaying treatment costs patients years of life on dialysis. The key is early diagnosis - yet 52% of patients wait over a year to get a correct diagnosis. Many see seven doctors before someone takes their symptoms seriously.

How Fast Does Each Cause Progress?

Not all kidney failure happens at the same speed. Here’s what the data shows:

- Diabetic kidney disease: From early protein leakage to kidney failure - about 8.7 years on average.

- Hypertensive kidney disease: Slower - around 12.3 years from diagnosis to ESRD.

- Glomerulonephritis: Highly variable. Some people decline in 5 years; others stay stable for decades.

The difference isn’t just time - it’s predictability. Diabetes follows a clear path: high blood sugar → protein in urine → declining GFR → failure. Hypertension is more gradual. Glomerulonephritis? It’s unpredictable. One person might have mild IgA nephropathy for 20 years. Another might crash into kidney failure in 5. That’s why regular monitoring matters more than ever.

What You Can Do - Before It’s Too Late

There’s no magic cure. But there are proven steps that work - if you start early.

- Test your urine yearly. If you have diabetes or high blood pressure, ask for a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). A result over 30 mg/g means early kidney damage.

- Check your eGFR. This blood test estimates kidney function. If it drops below 60 mL/min/1.73m², you need a nephrologist.

- Take your meds. ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and SGLT2 inhibitors aren’t optional. They’re kidney protectors.

- Watch your salt and protein. Too much salt raises blood pressure. Too much protein stresses damaged kidneys. Aim for 0.8 grams per kg of body weight daily - no more.

- Don’t ignore symptoms. Foamy urine? Swollen ankles? Unexplained fatigue? These aren’t normal. They’re warnings.

One patient in Bristol told me, "I thought my tiredness was just aging. Turns out, my kidneys were failing." She started SGLT2 inhibitors after spotting protein in her urine. Two years later, her kidney function stabilized. She’s not on dialysis. She’s still working. She’s still walking her dog.

The Bigger Picture

Kidney disease affects 850 million people worldwide. In the UK, diabetes and hypertension are the twin engines driving the crisis. The cost? Over £1 billion a year just in NHS spending. But here’s the hope: if we catch kidney damage early, we can prevent up to half of all future cases.

The tools are here - blood tests, effective drugs, better guidelines. What’s missing is awareness. Most people know diabetes causes heart problems. Few know it’s the #1 cause of kidney failure. Most know high blood pressure is dangerous. Few realize it’s silently destroying their kidneys.

It’s not about fear. It’s about action. One simple urine test. One annual blood check. One conversation with your GP. That’s all it takes to change the outcome.

Can you reverse kidney damage from diabetes?

Early-stage kidney damage from diabetes can be slowed or even partially reversed if caught in time. If you have microalbuminuria (30-300 mg/g of protein in urine) and get your HbA1c below 7%, start an SGLT2 inhibitor, and control your blood pressure, studies show kidney function can stabilize - and in some cases, improve. But once scarring (fibrosis) sets in, it’s permanent. The goal isn’t reversal - it’s stopping further damage.

Is glomerulonephritis hereditary?

Most forms of glomerulonephritis aren’t directly inherited. But some genetic factors can increase risk. For example, IgA nephropathy is more common in people with certain immune system genes, and it tends to run in families in some populations - especially in Asia. Lupus nephritis is linked to autoimmune conditions like SLE, which can have a genetic component. Still, having a relative with glomerulonephritis doesn’t mean you’ll get it - but it does mean you should be more vigilant about kidney checks.

Can high blood pressure cause kidney failure without diabetes?

Absolutely. Hypertension alone is responsible for nearly 30% of all kidney failure cases in the US and UK. Even without diabetes, long-term uncontrolled high blood pressure damages the tiny arteries in the kidneys, reducing blood flow and causing scarring. This is called hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Many people don’t realize their kidneys are failing because high blood pressure often has no symptoms. Regular kidney function tests are critical for anyone with hypertension.

Do I need a kidney biopsy if I have protein in my urine?

Not always. If you have diabetes or long-standing high blood pressure and protein in your urine, your doctor may start treatment without a biopsy - especially if your case looks typical. But if you’re younger, have blood in your urine, no history of diabetes or hypertension, or if your kidney function drops quickly, a biopsy is often needed. It tells you exactly what’s causing the damage - whether it’s IgA nephropathy, lupus, or something else - and guides treatment.

What’s the best diet for someone with early kidney damage?

The DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) is the most proven. It’s low in salt, processed foods, and saturated fat, and high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean protein. Protein intake should be moderate - around 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight. Too much protein strains damaged kidneys. Avoid high-sodium foods like canned soups, processed meats, and takeaways. Stay hydrated, but don’t overdo fluids unless your doctor says so. A renal dietitian can help tailor this to your needs.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve been told you have early kidney damage - whether from diabetes, high blood pressure, or something else - don’t panic. But don’t wait either. Your next steps are simple:

- Book a urine test and eGFR blood test if you haven’t had one in the last year.

- Ask your doctor if you’re on the right meds - especially ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Get a referral to a kidney specialist if your protein level is over 30 mg/g or your eGFR is below 60.

- Start tracking your blood pressure at home. Write it down. Bring it to your appointments.

Kidney failure isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable - if you act before the damage becomes permanent. The clock is ticking. But you still have time to turn it around.