Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Recognition Tool

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Assessment

Identify whether your symptoms might be opioid-induced hyperalgesia rather than tolerance or other causes

This tool helps you understand if your pain symptoms might be caused by opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) rather than tolerance or other conditions. OIH occurs when long-term opioid use actually makes pain worse. It's not a medical diagnosis but can help you have a more informed discussion with your doctor.

Your Assessment Results

Imagine taking more painkillers because your pain is getting worse-only to find out the medicine itself is making the pain worse. It sounds backwards, but it’s real. This is opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), a hidden side effect of long-term opioid use that tricks both patients and doctors into thinking the pain is getting worse because the treatment isn’t working. In reality, the opioids are partly to blame.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia isn’t tolerance. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH is different: your nervous system becomes oversensitive to pain, so even mild touches or normal movements hurt more than they should. You might start feeling pain in places you never did before, or light pressure from clothing feels like burning.

This isn’t just theory. It was first seen in rats in 1971 when repeated morphine injections made them more sensitive to pain. Since then, human studies have confirmed it. Patients on long-term opioids-especially high doses of morphine or hydromorphone-often report pain spreading beyond the original injury site. A person with lower back pain might suddenly feel pain in their legs, hips, or even their arms, even though nothing new has happened physically.

It’s not rare. Studies estimate 2-10% of people on long-term opioid therapy develop OIH. But because it looks so much like tolerance or disease progression, many cases go undiagnosed-or worse, misdiagnosed as needing even higher doses.

How OIH Differs from Tolerance and Other Problems

Confusing OIH with tolerance is common-and dangerous. Here’s how to tell them apart:

- Tolerance: You need more opioid to get the same level of pain relief. The pain itself doesn’t feel worse, just harder to control.

- OIH: Pain feels more intense, spreads to new areas, and hurts from things that shouldn’t hurt-like a light brush of fabric or a gentle touch.

There’s also allodynia-a hallmark sign of OIH. This is when something harmless, like a cotton ball or a breeze, triggers sharp pain. It’s a red flag. You won’t see this in simple tolerance.

Other conditions can mimic OIH too: withdrawal symptoms, new injuries, nerve damage, or even depression. That’s why diagnosis is tricky. Doctors have to rule out everything else before considering OIH. One key clue? If reducing the opioid dose makes the pain better, that’s a strong sign it’s OIH-not tolerance.

Why Does This Happen? The Science Behind the Pain

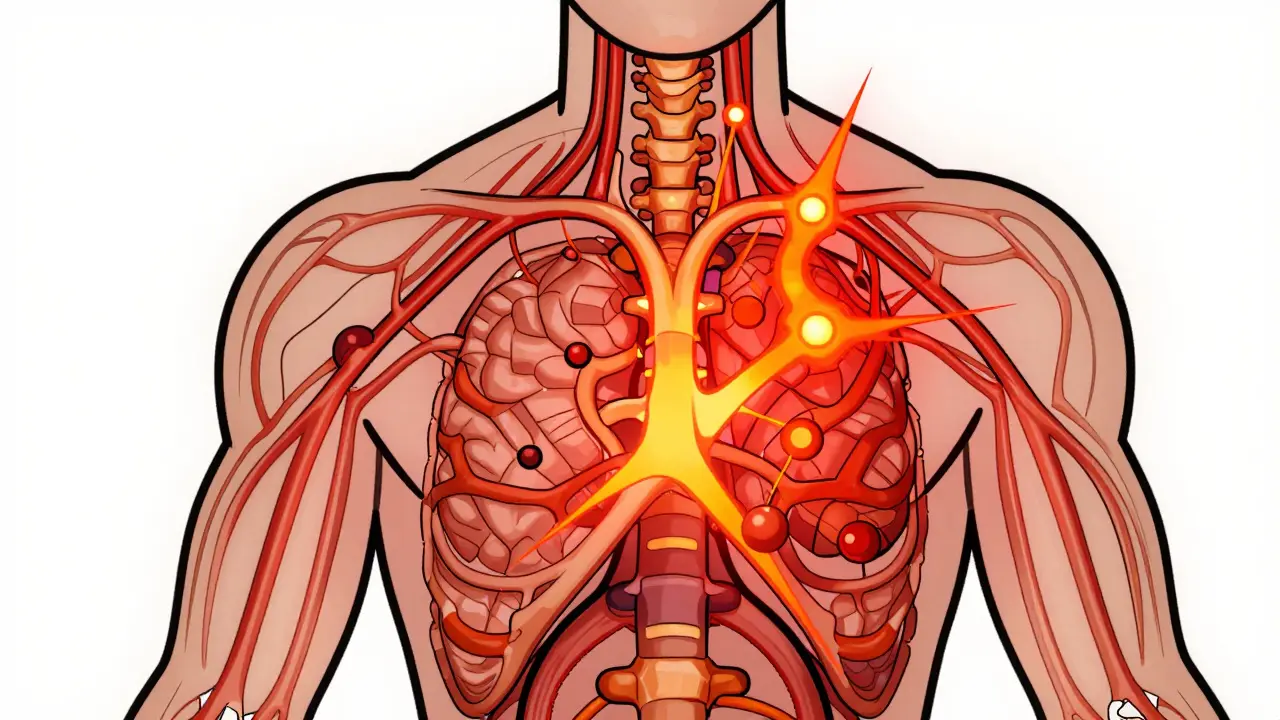

Opioids don’t just block pain-they also trigger changes in your nervous system that can amplify it. Here’s what’s happening inside your body:

- NMDA receptor activation: Opioids cause your brain and spinal cord to release more glutamate, a chemical that excites pain signals. This overactivates NMDA receptors, turning up the volume on pain.

- Dynorphin release: Your body starts producing dynorphin, a natural substance that actually increases pain sensitivity instead of reducing it.

- Descending facilitation: Normally, your brain sends signals down the spine to calm pain. With OIH, those signals flip-instead of calming pain, they turn it up.

- Toxic metabolites: In people with kidney problems, opioids break down into substances like morphine-3-glucuronide, which directly irritate nerve cells and worsen pain.

- Genetics: Some people have a gene variant (COMT) that makes them more likely to develop OIH. Their bodies break down pain-modulating chemicals like dopamine and norepinephrine slower, leaving the nervous system stuck in high-alert mode.

These changes create a feedback loop: more opioids → more pain sensitivity → more opioids → even more pain. It’s a spiral that’s hard to break without understanding what’s really going on.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on opioids gets OIH. But certain factors raise your risk:

- High-dose opioids, especially intravenous or long-acting forms

- Long-term use (more than 3-6 months)

- Renal impairment (kidney problems leading to metabolite buildup)

- History of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia or neuropathy

- Genetic predisposition (COMT gene variants)

- Previous exposure to high opioid doses during surgery

People in palliative care or those recovering from major surgeries are especially vulnerable. Studies show patients who get large opioid doses during surgery often need 20-30% more pain meds afterward-not because the surgery hurt more, but because their nervous system was primed for hyperalgesia.

How Is OIH Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test or scan for OIH. Diagnosis is based on clinical clues:

- Pain gets worse even though opioid doses are increased

- Pain spreads beyond the original area

- Allodynia or heightened sensitivity to touch, cold, or pressure

- No new injury, infection, or disease progression to explain the change

- Pain improves when opioid dose is lowered

Some clinics use quantitative sensory testing-applying controlled pressure, heat, or cold to measure pain thresholds. If thresholds drop significantly in areas far from the original pain site, it supports OIH. But these tests aren’t widely available. Most diagnoses come from careful history-taking and trial-and-error.

How Is It Treated?

The goal isn’t to stop opioids overnight-it’s to break the cycle safely. Here’s what works:

- Reduce the opioid dose: This sounds counterintuitive, but lowering the dose often reduces pain because you’re removing the trigger. A slow, supervised taper-over weeks or months-is key.

- Switch opioids (rotation): Switching to methadone or buprenorphine can help. Methadone blocks NMDA receptors, which directly counters the mechanism behind OIH. One study found patients on methadone needed 40% less pain medication after surgery than those on other opioids.

- Add NMDA blockers: Low-dose ketamine (given through IV or nasal spray) can calm the overactive pain signals. Magnesium sulfate, given intravenously, has shown similar effects.

- Use gabapentin or pregabalin: These drugs calm overactive nerves by targeting calcium channels involved in central sensitization. Doses typically range from 900-3600 mg/day for gabapentin or 150-600 mg/day for pregabalin.

- Non-drug therapies: Cognitive behavioral therapy helps retrain how the brain processes pain. Physical therapy, graded movement, and mindfulness practices can also reduce pain sensitivity over time.

There’s no one-size-fits-all plan. Treatment must be personalized, slow, and monitored closely. Rushing a taper can cause withdrawal or rebound pain. Too little reduction won’t break the cycle.

The Controversy: Is OIH Real-or Overdiagnosed?

Not all doctors agree on how common OIH really is. Some say it’s underrecognized. Others argue it’s overdiagnosed, and that what looks like OIH is just uncontrolled pain, anxiety, or withdrawal.

Dr. Stephan Schug, a leading pain expert in Australia, says the debate continues because symptoms overlap so much with other conditions. But experts like Dr. Perry Fine from the University of Utah insist OIH is a critical issue in chronic pain management-especially when patients are stuck on rising doses with no relief.

The American Pain Society recognizes OIH as real but admits many clinicians aren’t trained to spot it. In a 2020 survey, only 35% of pain specialists felt confident diagnosing it. That’s a problem. Without proper recognition, patients keep getting more opioids, making things worse.

What Should You Do If You Suspect OIH?

If you’ve been on opioids for months and your pain is getting worse despite higher doses, talk to your doctor. Ask:

- Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

- Have we ruled out other causes like nerve damage or new injuries?

- Would reducing my dose help, even if it feels scary?

- Could switching to methadone or adding gabapentin be an option?

Don’t stop opioids suddenly. That can cause dangerous withdrawal. But don’t keep increasing doses without asking why the pain is getting worse.

There’s hope. Many patients who switch treatment strategies report significant pain reduction-even if they end up on lower opioid doses or none at all. The key is recognizing the pattern early and changing course before the nervous system becomes too sensitized.

Looking Ahead: What’s Next for OIH?

Researchers are working on better ways to detect OIH before it takes hold. Blood tests for biomarkers, genetic screening for COMT variants, and wearable sensors that track pain sensitivity are all in early trials. New drugs targeting kappa-opioid receptors or specific NMDA subtypes may offer pain relief without triggering hyperalgesia.

For now, the best defense is awareness. If you’re managing chronic pain with opioids, know that more isn’t always better. Sometimes, less is the path to real relief.