Opioid Use Disorder Risk Assessment

Assess Your Risk of Opioid Use Disorder

This tool helps you understand the difference between physical dependence (normal bodily adaptation) and addiction (Opioid Use Disorder). Based on the DSM-5 criteria, which requires at least 2 symptoms to diagnose OUD.

Important: This is not a diagnostic tool. If you suspect addiction, speak with a healthcare professional.

Your Risk Assessment

0 of 11 criteria met

Many people think if someone takes opioids for a long time and feels sick when they stop, they’re addicted. That’s not true. And this misunderstanding is putting people at risk - not just from drugs, but from being denied the pain relief they need.

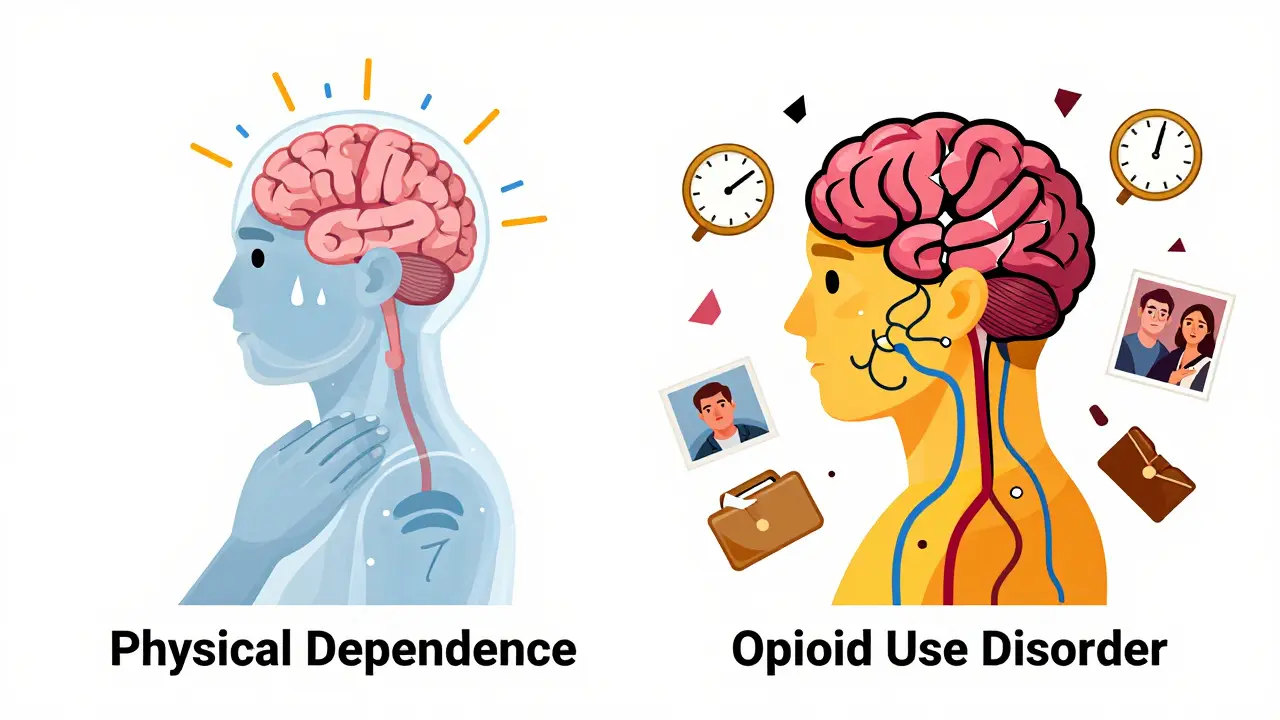

Physical dependence and addiction are not the same thing. One is a normal bodily reaction. The other is a brain disorder. Confusing them leads to stigma, unnecessary suffering, and even death.

What Is Physical Dependence?

Physical dependence happens when your body gets used to having a drug in your system. It’s not a choice. It’s biology.

If you take opioids like oxycodone, hydrocodone, or morphine for more than a few weeks - especially at doses above 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day - your brain adjusts. It changes how it produces chemicals like norepinephrine. When you stop taking the drug, your body doesn’t know how to function without it. That’s when withdrawal kicks in.

Withdrawal symptoms are real and unpleasant. Nausea hits 92% of people. Vomiting? 85%. Sweating, anxiety, diarrhea, yawning - all common. These aren’t signs of addiction. They’re signs your body adapted. It’s like how your body adjusts to caffeine. Stop drinking coffee after months, and you get headaches. That doesn’t mean you’re addicted to coffee. It means your brain changed.

Studies show nearly 100% of patients on long-term opioid therapy develop physical dependence. That’s not rare. It’s expected. And it’s not dangerous by itself. You can manage it safely with a slow, medical taper - usually reducing the dose by 5-10% every 2 to 4 weeks. Done right, withdrawal lasts days to weeks, then fades.

What Is Addiction? (Opioid Use Disorder)

Addiction - now called Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) in medical terms - is not about physical withdrawal. It’s about loss of control.

People with OUD keep using opioids even when it destroys their lives. They lie. They steal. They lose jobs. They risk overdose. They can’t stop, even when they want to.

This isn’t weakness. It’s brain disease. Addiction changes the reward system. The dopamine pathways in the brain’s nucleus accumbens get rewired. The prefrontal cortex - the part that makes decisions and controls impulses - weakens. Imaging studies show these changes last for years, even after stopping the drug.

The DSM-5, the standard guide doctors use to diagnose mental health conditions, lists 11 criteria for OUD. You need at least two to be diagnosed. These include:

- Craving the drug (83% of severe cases)

- Using more than intended

- Failing to cut down

- Spending too much time getting or using the drug

- Ignoring responsibilities

- Continuing use despite relationship problems

- Giving up hobbies

- Using in dangerous situations

- Needing more to get the same effect (tolerance)

- Withdrawal symptoms

- Using to avoid withdrawal

Crucially, tolerance and withdrawal - the same signs of physical dependence - are listed here too. But they’re only two of eleven. You can have them without OUD. You can’t have OUD without behavioral damage.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Here’s what the data shows: Most people on opioids don’t become addicted.

A 2017 study in Pain Medicine found that while almost everyone on long-term opioids becomes physically dependent, only about 8% develop OUD. Another study from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed 9.9 million Americans misused prescription painkillers - but only 1.7 million met the clinical criteria for addiction.

And here’s the kicker: If you’re prescribed opioids after surgery and use them exactly as directed, your risk of developing OUD is between 0.7% and 1%. That’s less than 1 in 100. Yet many patients stop their meds out of fear - even when they’re still in pain.

A 2020 study found 68% of chronic pain patients thought withdrawal meant they were addicted. So they quit. And many ended up in worse pain, or worse, turned to street drugs like heroin because they couldn’t get prescriptions anymore.

Why This Distinction Matters

When doctors mistake dependence for addiction, they do harm.

Patients are abruptly cut off from medication. Their pain flares. Their mental health crashes. Some turn to illegal drugs. The CDC estimates that after the 2016 opioid prescribing guidelines, prescriptions dropped by 44% - but overdose deaths from illicit opioids rose by over 20,000 in the following years.

The American Medical Association passed a resolution in 2021 telling doctors: Don’t stop opioids just because a patient is physically dependent. If the drug is helping with pain and the patient isn’t using it compulsively, keep prescribing. Taper slowly. Monitor. Don’t panic.

Dr. Nora Volkow, head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, says it plainly: “Physical dependence is a normal physiological adaptation. Addiction reflects pathologic changes in brain circuits that govern motivation and behavior.”

And Dr. Andrew Kolodny, a leading opioid policy expert, says conflating the two has caused the undertreatment of pain and turned patients into suspects.

How Doctors Tell the Difference

There’s no single blood test. But there are tools.

Doctors use the Opioid Risk Tool to screen for risk factors like family history of addiction, past mental health issues, or substance use before age 18. About 24% of patients are flagged as high-risk.

They use the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) to measure withdrawal severity. A score above 12 means moderate withdrawal - treatable with medication like lofexidine, approved by the FDA in 2023.

For OUD diagnosis, trained clinicians use the full DSM-5 checklist. It’s 94% accurate when done right.

Neuroimaging is starting to help too. A 2023 study in the Journal of Neuroscience found fMRI scans could distinguish physical dependence from OUD with 89% accuracy by measuring how the prefrontal cortex reacts to drug cues. This could be routine in clinics within five years.

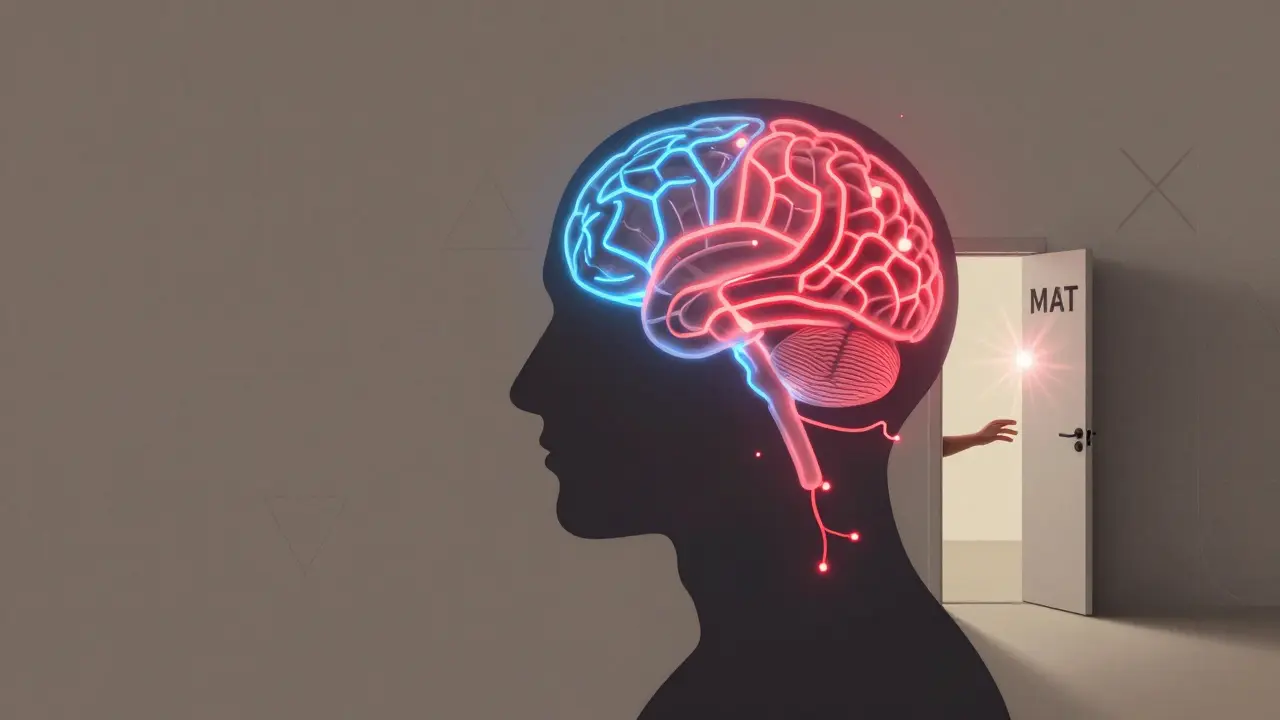

What Treatment Looks Like

Physical dependence? Taper slowly. Use medications like clonidine or lofexidine to ease withdrawal. Support with counseling if needed. Done in weeks.

Opioid Use Disorder? That’s a chronic condition. It needs long-term care.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is the gold standard. Buprenorphine reduces overdose deaths by 70-80%. Methadone cuts them by 50%. These aren’t replacing one drug with another. They’re stabilizing brain chemistry so people can rebuild their lives.

And MAT works best with therapy - cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, peer support. People need help dealing with trauma, stress, and the reasons they started using in the first place.

Insurance now covers MAT in 98% of commercial plans. But only 67% have clear protocols for managing physical dependence in pain patients. That gap needs closing.

Real Stories, Real Consequences

One Reddit user wrote: “I tapered off 60 MME/day oxycodone over eight weeks. Had withdrawal for 10 days - nausea, shaking, insomnia. But I never craved it outside of the schedule. I never stole. I never lied. I just needed it for my back.”

Another patient in the NIDA archive said: “After my surgery, I kept refilling prescriptions I didn’t need. I stole money from my mom. I drove two hours just to get more pills. I lost my job. I didn’t care. I just had to have them.”

One is physical dependence. The other is addiction. One can be managed. The other must be treated.

What You Should Do

If you’re on opioids for pain:

- Don’t panic if you feel sick when you miss a dose. That’s normal.

- Ask your doctor about your risk for OUD. Use the Opioid Risk Tool if they don’t offer it.

- Never stop cold turkey. Work with your provider on a taper plan.

- Know the signs of addiction: lying, stealing, using despite harm, losing control.

- Ask about MAT if you think you might have OUD. It saves lives.

If you know someone on opioids:

- Don’t assume they’re addicted because they take them regularly.

- Don’t shame them for withdrawal symptoms.

- Ask if they’re using the meds as prescribed.

- Encourage them to talk to their doctor if they feel out of control.

The opioid crisis didn’t start because people got addicted to painkillers. It started because we told people they would get addicted - even if they didn’t. And then we abandoned them when they needed help.

Understanding the difference between physical dependence and addiction isn’t just medical. It’s moral.

Can you be physically dependent on opioids without being addicted?

Yes. Nearly everyone who takes opioids for more than a few weeks becomes physically dependent. That means their body adapts and withdrawal symptoms appear if they stop. But addiction - or Opioid Use Disorder - requires compulsive use, loss of control, and harm to life, relationships, or health. Most people on long-term opioids for pain are dependent, not addicted.

Does withdrawal mean I’m addicted?

No. Withdrawal is a sign of physical dependence, not addiction. It’s your body adjusting after regular exposure to a drug. Many people experience withdrawal from medications like antidepressants or beta-blockers without being addicted. Addiction is about behavior - using despite harm, craving uncontrollably, losing control over use.

How do I know if I have Opioid Use Disorder?

OUD is diagnosed when you have at least two of 11 symptoms in a year, including cravings, using more than intended, failing to cut down, neglecting responsibilities, continuing use despite harm, and giving up activities. If you’re using opioids to avoid withdrawal but still managing your life - you likely have dependence. If you’re lying, stealing, losing jobs, or risking overdose - you may have OUD. Talk to a doctor or addiction specialist for evaluation.

Is tapering off opioids safe?

Yes, if done slowly under medical supervision. The CDC recommends reducing doses by 5-10% every 2-4 weeks. For higher doses (over 100 MME/day), slow down to 5% per month. Medications like lofexidine can ease withdrawal symptoms. Never stop abruptly - it can cause severe discomfort and increase risk of relapse or overdose if you return to use later.

What’s the best treatment for Opioid Use Disorder?

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) with buprenorphine or methadone is the most effective. These medications reduce cravings, block overdose effects, and allow people to stabilize. Combined with counseling - like cognitive behavioral therapy - they improve outcomes dramatically. Buprenorphine reduces overdose deaths by 70-80%. MAT isn’t replacing one drug with another. It’s treating a brain disorder, like insulin for diabetes.

Why do doctors sometimes stop opioid prescriptions too quickly?

Many doctors confuse physical dependence with addiction because they were trained to fear opioids. Fear of regulatory penalties, stigma, and misinformation led to abrupt discontinuation. But guidelines from the CDC and AMA now say: don’t stop opioids just because a patient is dependent. If the benefits outweigh the risks and there’s no addiction, continue treatment. Taper slowly if needed. Stopping too fast can push patients toward illegal drugs.

Can you become addicted to opioids after surgery?

It’s rare. Studies show only 0.7% to 1% of opioid-naïve patients develop Opioid Use Disorder after surgery if they use opioids exactly as prescribed. Most people stop after their pain improves. Addiction usually develops in people with existing risk factors - past substance use, mental health conditions, or chronic pain. Taking opioids for a short time after surgery is not a guaranteed path to addiction.