When you take a pill, you expect it to help. But sometimes, it does something you didn’t sign up for. A headache turns into a rash. A blood pressure med makes you dizzy. Or worse - you wake up with blisters on your skin after taking a common antibiotic. These aren’t just bad luck. They’re adverse drug reactions, and they fall into two very different categories: predictable and unpredictable.

What Makes a Side Effect Predictable?

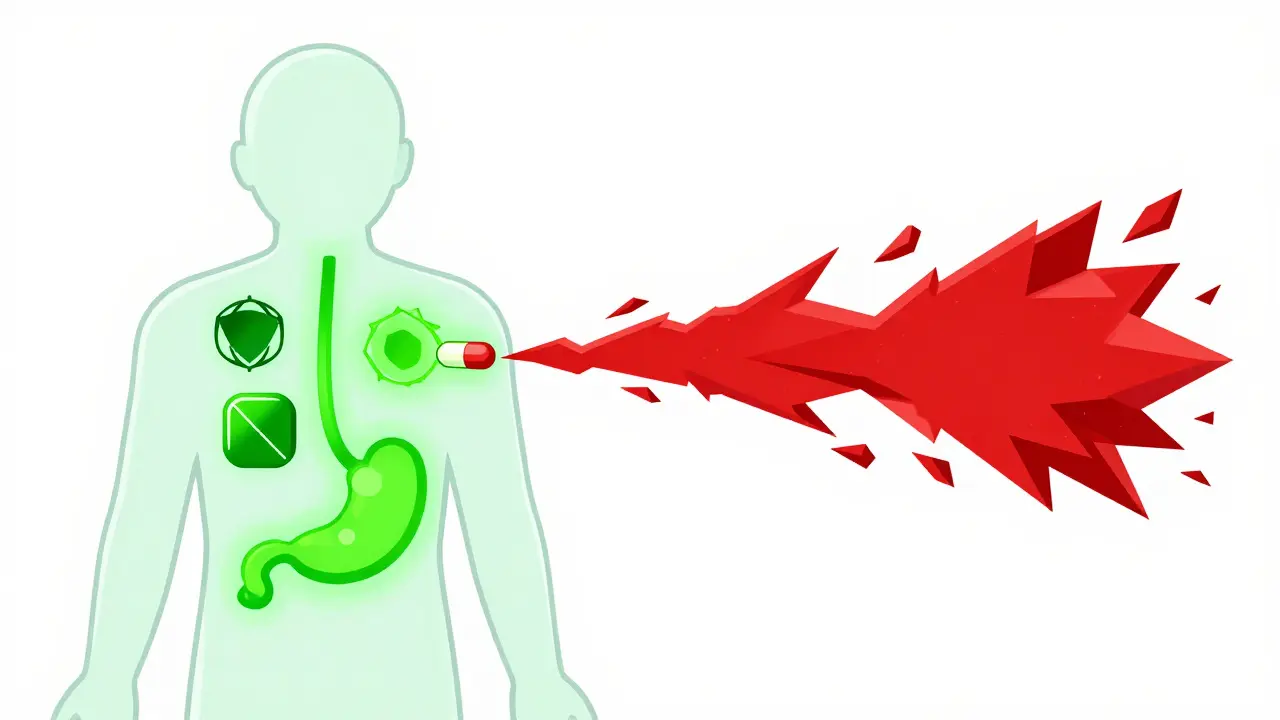

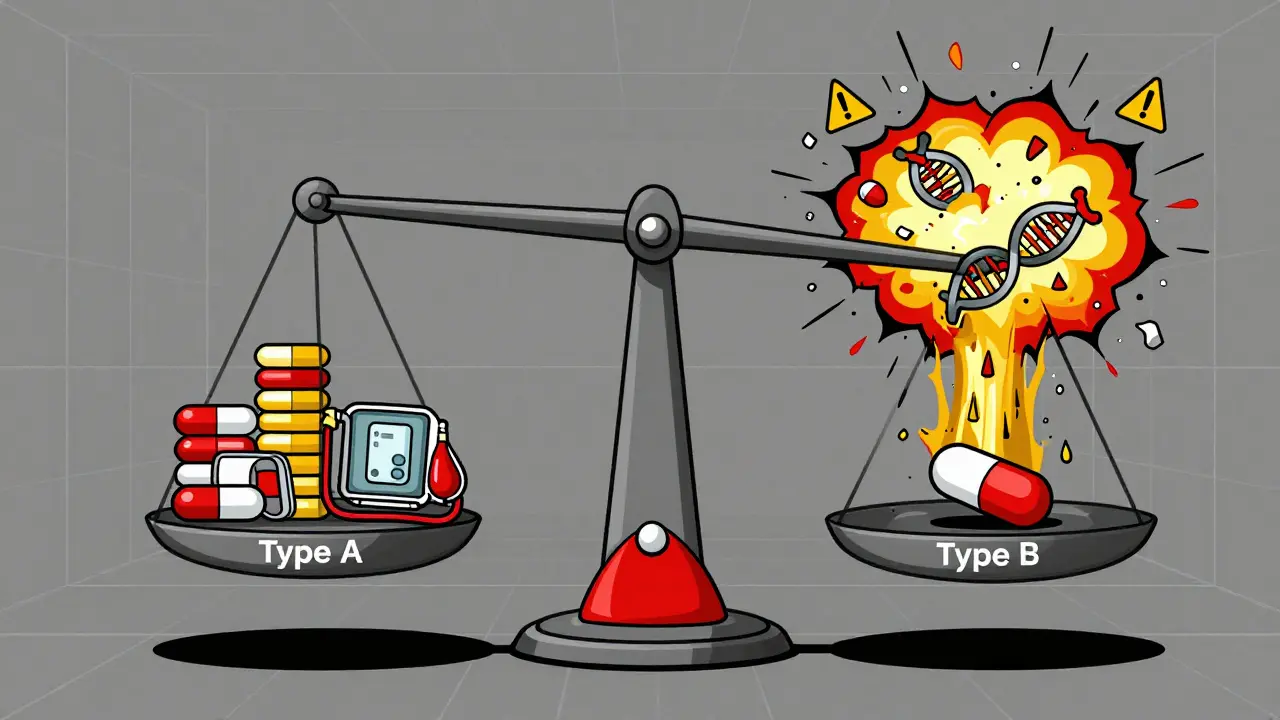

Predictable side effects - known as Type A reactions - are the most common. About 75 to 80% of all bad reactions to medicines fall into this group. They happen because the drug does exactly what it’s supposed to do… just too much, or in the wrong place. Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen. They reduce pain and inflammation by blocking enzymes that cause swelling. But those same enzymes also protect your stomach lining. So when you take too much, or take it too long, you get stomach bleeding. That’s not a glitch. It’s a direct result of the drug’s mechanism. The higher the dose, the higher the risk. Studies show stomach bleeding risk jumps from 1-2% at normal doses to 10-15% at high doses. Same thing with blood pressure meds. If your dose is too high, your blood pressure can drop too low. Or with metformin - a diabetes drug - it can cause low blood sugar, especially if you skip meals. These reactions are dose-dependent. They’re not rare. They’re expected. And they’re often fixable. The good news? Most Type A reactions are reversible. Lower the dose. Stop the drug. Symptoms fade. Mortality is low. That’s why doctors monitor kidney function with NSAIDs, check blood sugar with diabetes meds, and watch for dizziness with heart medications. These aren’t random checks. They’re standard safety steps built into how we use these drugs.What Makes a Side Effect Unpredictable?

Then there’s the other kind. The kind that makes even experienced doctors pause. Unpredictable side effects - Type B reactions - are rare. Only 20 to 25% of all adverse reactions. But they’re dangerous. And they make no sense. A healthy 24-year-old takes sulfamethoxazole for a urinary tract infection. Two days later, their skin starts peeling off. Over 30% of their body is covered in blisters. They’re diagnosed with toxic epidermal necrolysis - a life-threatening condition. No overdose. No prior history. No warning. Just… this. That’s Type B. It’s not about how much you took. It’s about who you are. Your genes. Your immune system. Your body’s weird, one-in-10,000 response. Some of the most serious examples:- Stevens-Johnson syndrome from carbamazepine - linked to the HLA-B*1502 gene, especially in people of Han Chinese descent.

- Severe allergic reactions to penicillin - even one pill can trigger anaphylaxis.

- Drug-induced hemolysis in people with G6PD deficiency - a common enzyme disorder where certain drugs destroy red blood cells.

- Vancomycin causing “red man syndrome” - not an allergy, but a direct trigger of mast cells that release histamine.

Why This Distinction Matters

Knowing the difference isn’t just academic. It changes how doctors treat you. For Type A reactions, the solution is straightforward: adjust the dose. Switch the drug. Add a protective medication like a proton pump inhibitor for NSAID users. These are routine fixes. They’re built into clinical guidelines. And they work. Type B? That’s a different game. You can’t just lower the dose. You can’t monitor your way out of it. The only real protection is prevention - and that means knowing who’s at risk before you give the drug. That’s where genetic testing comes in. Before prescribing abacavir (an HIV drug), doctors test for HLA-B*5701. If you have it, you don’t get the drug. Period. This simple step has cut abacavir-related hypersensitivity from 5% to less than 1%. Same with carbamazepine in Asian populations. Test for HLA-B*1502. If positive, avoid the drug. Simple. Life-saving. But here’s the problem: we can only screen for a few of these. Right now, pharmacogenetic testing covers about 30% of the high-risk Type B reactions. That means 70% of people are still flying blind. A patient could develop Stevens-Johnson syndrome from acetaminophen - yes, Tylenol - with no known genetic marker. No warning. No test. Just bad luck.The Hidden Cost of Side Effects

It’s not just about health. It’s about money. The U.S. spends $30.1 billion a year treating adverse drug reactions. Type A reactions - the predictable ones - cost $22.6 billion. Type B? Only 25% of cases, but $7.5 billion. Why? Because one severe Type B reaction can mean weeks in the ICU, skin grafts, long-term disability, or death. The treatment costs are massive. That’s why the pharmacovigilance industry - the system that tracks drug safety - is growing fast. It was worth $587 million in 2022. By 2027, it’s expected to hit $1.2 billion. Hospitals are investing in AI tools that scan electronic records for early signs of reactions. The FDA requires Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for drugs with high Type B risk. That means special training, patient registries, and restricted distribution. And yet - only 42% of serious side effects are correctly classified when first reported. Doctors miss the difference. Nurses don’t know the genetic flags. Patients don’t realize a rash could be deadly. That’s why training matters. It takes 6 to 12 months of clinical experience for new doctors to confidently tell Type A from Type B.

What’s Changing - and What’s Not

Technology is helping. In 2023, the FDA approved the first AI tool that uses your genes to guide warfarin dosing - reducing bleeding risk. The NIH’s All of Us program found 17 new gene-drug links, including one for phenytoin in non-Asian patients. That’s progress. But AI still struggles with Type B reactions. Google Health’s system predicted Type A reactions with 89% accuracy. For Type B? Only 47%. Why? Because they’re not just genetic. They’re messy. Your environment. Your gut bacteria. Your immune history. Your stress levels. All of it plays a role. We don’t have the full picture yet. The World Health Organization says Type B reactions will remain an “inherent challenge of pharmacotherapy.” That means they won’t disappear. They’ll always be part of taking medicine.What You Can Do

You’re not powerless.- Know your meds. If you’re prescribed a new drug, ask: “What are the common side effects? Are there any rare but serious ones I should watch for?”

- Tell your doctor about every reaction you’ve ever had - even if it was years ago. A rash from an old antibiotic? Mention it. A dizzy spell after a painkiller? Say it.

- If you have a family history of severe drug reactions, ask about genetic testing. It’s not routine yet - but it’s becoming more available.

- Don’t ignore early warning signs. A fever, a rash, swelling, trouble breathing - don’t wait. Call your doctor. Or go to urgent care. Type B reactions can escalate fast.

Are all side effects dangerous?

No. Many side effects are mild and temporary - like nausea from antibiotics or drowsiness from antihistamines. These are often predictable (Type A) and go away as your body adjusts. But some reactions, especially unpredictable ones (Type B), can be life-threatening. Always report new or worsening symptoms to your doctor, even if they seem minor.

Can I prevent unpredictable side effects?

Sometimes. For certain drugs like abacavir or carbamazepine, genetic testing can identify high-risk individuals before the drug is even prescribed. But we only have tests for a small number of these reactions. For most, prevention means avoiding the drug entirely if you’ve had a reaction before, or watching closely for early signs like rash, fever, or swelling. There’s no foolproof way yet - but awareness helps.

Why do some people react badly to a drug while others don’t?

It’s often genetic. Some people have variations in genes that affect how their body processes drugs or how their immune system responds. For example, the HLA-B*1502 gene makes people of Southeast Asian descent far more likely to develop a dangerous skin reaction from carbamazepine. But genes aren’t the whole story. Environment, age, other illnesses, and even gut bacteria can play a role - which is why these reactions are so hard to predict.

Is it safe to keep taking a drug if I had a mild side effect?

It depends. Mild, predictable side effects - like occasional dizziness from blood pressure meds - can often be managed by adjusting the dose or timing. But if you had a rash, swelling, trouble breathing, or blistering, stop the drug and contact your doctor immediately. These could be signs of a serious Type B reaction, and continuing the drug could be fatal.

Do pharmacists know about these differences?

Yes, trained pharmacists are taught to recognize and flag both predictable and unpredictable reactions. Many pharmacies now use electronic alerts that warn when a patient’s profile matches a high-risk gene or past reaction. But not all systems are connected, and not all pharmacists have full access to medical history. Always tell your pharmacist about every drug you’ve taken - including over-the-counter and herbal products.

Can I be tested for genetic risks before taking a new drug?

It’s possible, but not yet routine for most drugs. Testing is standard before taking abacavir, carbamazepine, or certain cancer drugs. For others, it’s still experimental or not widely available. Ask your doctor if genetic testing is recommended for your specific medication. If you’ve had a serious reaction before, you may be a candidate for broader testing through research programs or specialized clinics.