Every year, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, just as effective for most people, and save the healthcare system billions. But sometimes, a doctor insists on a brand-name drug-even when a generic is available. That’s not a mistake. It’s called a prescriber override, and it’s a legal tool built into state pharmacy laws to protect patients when generics just won’t do.

Why Do Doctors Override Generic Substitution?

It’s not about preference. It’s about safety. For certain medications, even tiny differences in how a generic is made can cause serious problems. Take levothyroxine, the drug used to treat hypothyroidism. The body is extremely sensitive to small changes in hormone levels. A patient stable on one brand might have a heart palpitation or thyroid storm if switched to a generic with slightly different absorption rates. The FDA calls these drugs “narrow therapeutic index” medications-meaning the difference between a safe dose and a dangerous one is razor-thin. Other cases include patients with documented allergies to inactive ingredients in generics-like lactose, dyes, or fillers. Or patients who’ve tried multiple generics and had clear therapeutic failure: their symptoms returned, their lab values went off track, their quality of life dropped. In those situations, the doctor isn’t being stubborn. They’re responding to real clinical evidence.How Prescriber Override Works: The DAW-1 Code

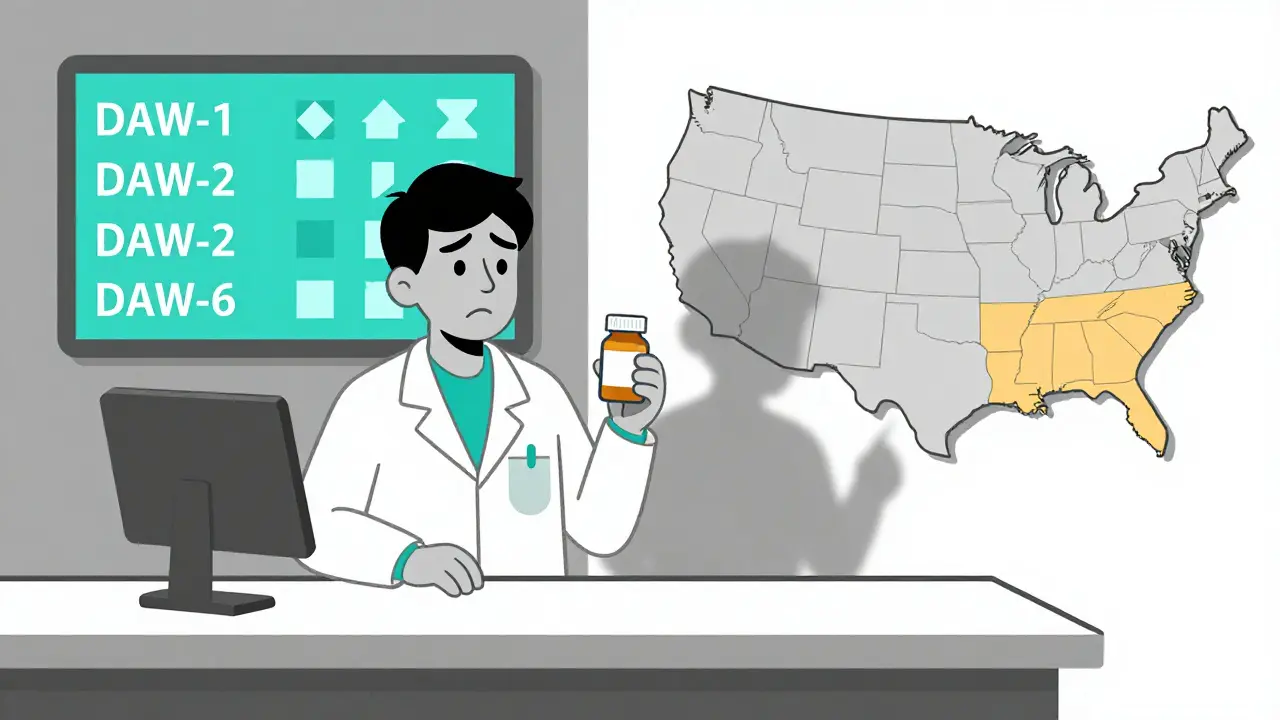

When a doctor wants to block a generic substitution, they don’t just write “no generics.” They use a standardized code called DAW-1, which stands for “Dispense as Written.” This code tells the pharmacy: Do not substitute. Give exactly what’s prescribed. It’s part of the NCPDP Telecommunications Standard, the universal language of e-prescribing. But here’s the catch: DAW-1 isn’t the only code. There are nine of them. DAW-2 means the patient asked for the brand. DAW-3 means the pharmacist chose the generic. DAW-6 means an override was applied. The system is designed to track why a drug was dispensed the way it was. But if the code isn’t entered correctly, the pharmacy system might still substitute-and that’s when things go wrong.State Laws Are a Patchwork

There’s no federal rule that says how a prescriber override must be documented. Every state has its own rules. In Illinois, the doctor must check a box labeled “May Not Substitute.” In Kentucky, they must write “Brand Medically Necessary” by hand. In Michigan, they need to write “DAW” or “Dispense as Written.” In Oregon, they can call, text, or email the pharmacy. In Texas, the prescription form has two lines-one for the drug, one for the override note. This mess creates real problems. A doctor in Pennsylvania writes “Do Not Substitute” on a prescription. The patient travels to a pharmacy in New York. The pharmacist doesn’t recognize the phrase. They substitute the generic. The patient has a seizure. That’s not hypothetical. It’s happened. A 2022 survey of 1,247 physicians on Sermo found that 63% had run into issues with state-specific override rules. Forty-one percent said their electronic health records didn’t have the right templates. Thirty-seven percent said pharmacies kept rejecting their override requests because the documentation didn’t match local requirements.

What Happens When Overrides Go Wrong?

The cost of a wrong override is high. A 2017 study in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy found that DAW-1 prescriptions cost, on average, 32.7% more than substituted generics. That’s billions in extra spending every year. But the bigger risk is clinical. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices tracked 27 adverse events between 2018 and 2022 linked to inappropriate substitution of warfarin, phenytoin, or levothyroxine. One Reddit post from a doctor in June 2023 described a patient hospitalized for thyroid storm after a pharmacy substituted levothyroxine-even though the prescription had DAW-1. The pharmacy claimed they didn’t see the override because it was buried in a dropdown menu. Even worse: many doctors don’t know the rules. A national survey found only 58.3% of physicians correctly understood their state’s override requirements. One in five unintentionally allowed substitutions because they didn’t document properly.How to Get It Right

Doctors who use overrides correctly follow three steps:- Know your state’s rules. Check the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s interactive map. It’s updated quarterly and shows exactly what’s required in your state.

- Use the right code and format. Don’t write “no generics.” Write “DAW-1” or “Dispense as Written” if your state allows it. If your state requires handwriting, write it clearly. If it requires a box, check it.

- Use your EHR correctly. Many electronic systems have templates for overrides. Customize them to match your state. If your system doesn’t have one, ask your vendor to add it. A 2021 study showed optimized EHR templates cut override processing time from 1.7 minutes to 0.9 minutes per prescription.

The Bigger Picture: Cost vs. Safety

Generics saved $2.2 trillion between 2010 and 2019. That’s huge. But the goal isn’t to cut costs at all costs. It’s to cut waste-without risking lives. Payers know this. Express Scripts reported in 2021 that 18.4% of brand-drug spending was avoidable because of inappropriate DAW-1 use. Meanwhile, Medicare Part D plans and commercial insurers now use DAW-1 as a trigger for prior authorization. If you write DAW-1 on a drug that doesn’t need it, your patient might face delays-or even denial. The American Pharmacists Association estimates that only 5-7% of prescriptions truly require an override. The rest? They’re either misunderstandings, lazy documentation, or fear of liability.What’s Changing?

In 2023, Congress introduced the Standardized Prescriber Override Protocol Act. It’s still in committee, but if it passes, it would create one national standard for how overrides are requested and documented. That would end the state-by-state chaos. The FDA is also updating the Orange Book-the official list of therapeutically equivalent drugs. Version 4.0, released in January 2023, now includes biosimilar interchangeability codes. That means in the future, overrides won’t just apply to small-molecule generics. They’ll apply to complex biologics too. E-prescribing systems are catching up. By late 2024, the NCPDP’s SCRIPT 201905 standard will embed override requirements directly into the e-script. No more typing notes. No more checkboxes. The system will auto-populate the right DAW code based on the drug and the prescriber’s selection.Bottom Line: Override When Needed. Document When You Do.

Prescriber override isn’t a loophole. It’s a safety valve. Used right, it protects patients who need brand-name drugs. Used wrong, it drives up costs and causes harm. If you’re a doctor: Know your state’s rules. Use the right code. Don’t guess. If you’re a pharmacist: Verify the override. Don’t assume. If you’re a patient: Ask. If your doctor says “no generics,” ask why. And if you’re switched anyway, speak up. The system isn’t perfect. But it works-if everyone does their part.Can any doctor override generic substitution?

Yes, any licensed prescriber-doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants-can override generic substitution if they believe it’s medically necessary. But they must follow their state’s documentation rules. In some states, only certain providers can use specific override codes. Always check your state’s pharmacy board guidelines.

What happens if a pharmacy ignores a DAW-1 override?

If a pharmacy substitutes a drug despite a valid DAW-1 code, it’s a violation of state law. The prescriber can file a complaint with the state board of pharmacy. The pharmacy may face fines, license review, or mandatory training. Patients who are harmed can seek legal recourse. But enforcement varies by state, and many cases go unreported because patients don’t realize substitution occurred.

Are brand-name drugs always better than generics?

No. For the vast majority of drugs, generics are just as safe and effective. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. The only exceptions are narrow therapeutic index drugs-like warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, and some anti-seizure medications-where even small differences can cause harm.

Can patients request a brand-name drug even if the doctor didn’t override?

Yes. That’s called DAW-2. The patient can ask the pharmacist for the brand, even if the doctor didn’t write it. But the patient usually pays the difference in cost. Some insurance plans won’t cover it unless the doctor has written DAW-1. Always check with your insurer before asking.

How do I know if my medication has a generic that’s truly equivalent?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book online. Search your drug name. If it has an “A” rating, it’s considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand. If it has a “B” rating, it’s not. For narrow therapeutic index drugs, even an “A” rating doesn’t guarantee the same effect for every patient. Talk to your doctor before switching.

Why do some pharmacies still substitute even when DAW-1 is written?

There are three common reasons: 1) The override wasn’t entered correctly in the e-prescribing system-maybe the doctor typed “no generic” instead of “DAW-1.” 2) The pharmacy’s software didn’t recognize the code because it’s outdated. 3) The prescription was handwritten and the notation was unclear. Always confirm with the pharmacy that your override was processed.

Is prescriber override becoming more common?

Yes. Between 2020 and 2022, DAW-1 usage rose by 22.3% in California’s Medi-Cal program. Anticonvulsants and psychiatric drugs have the highest override rates-over 14% and 12% respectively. This reflects growing awareness of bioequivalence issues in sensitive populations. But experts warn that much of the increase may be due to confusion, not clinical need.

What should I do if my insurance denies my brand-name drug even with DAW-1?

Ask your doctor to file a prior authorization. Many insurers require this even with DAW-1 for high-cost drugs. Your doctor should include clinical notes explaining why the generic failed or why the brand is medically necessary. If denied, you can appeal. Some states have patient advocacy offices that help with these appeals.